Harps of seraphs

I

Mademoiselle, when you have read this letter, if you ever should read it, my life will be in your hand, for I love you; and to me, the hope of being loved is life. Others, perhaps, ere now, have, in speaking of themselves, misused the words I must employ to depict the state of my soul; yet, I beseech you to believe in the truth of my expressions; though weak, they are sincere. Perhaps I ought not thus to proclaim my love. Indeed, my heart counselled me to wait in silence till my passion should touch you, that I might the better conceal it if its silent demonstrations should displease you; or till I could express it even more delicately than in words if I found favour in your eyes. However, after having listened for long to the coy fears that fill a youthful heart with alarms, I write in obedience to the instinct which drags useless lamentations from the dying.

It has needed all my courage to silence the pride of poverty, and to overleap the barriers which prejudice erects between you and me. I have had to smother many reflections to love you in spite of your wealth; and as I write to you, am I not in danger of the scorn which women often reserve for professions of love, which they accept only as one more tribute of flattery? But we cannot help rushing with all our might towards happiness, or being attracted to the life of love as a plant is to the light; we must have been very unhappy before we can conquer the torment, the anguish, of those secret deliberations when reason proves to us by a thousand arguments how barren our yearning must be if it remains buried in our hearts, and when hopes bid us dare everything.

I was happy when I admired you in silence; I was so lost in the contemplation of your beautiful soul, that only to see you left me hardly anything further to imagine. And I should not now have dared to address you if I had not heard that you were leaving. What misery has that one word brought upon me! Indeed, it is my despair that has shown me the extent of my attachment – it is unbounded. Mademoiselle, you will never know – at least, I hope you may never know – the anguish of dreading lest you should lose the only happiness that has dawned on you on earth, the only thing that has thrown a gleam of light in the darkness of misery. I understood yesterday that my life was no more in myself, but in you. There is but one woman in the world for me, as there is but one thought in my soul. I dare not tell you to what a state I am reduced by my love for you. I would have you only as a gift from yourself; I must therefore avoid showing myself to you in all the attractiveness of dejection – for is it not often more impressive to a noble soul than that of good fortune? There are many things I may not tell you. Indeed, I have too lofty a notion of love to taint it with ideas that are alien to its nature. If my soul is worthy of yours, any my life pure, your heart will have a sympathetic insight, and you will understand me!

It is the fate of man to offer himself to the woman who can make him believe in happiness; but it is your prerogative to reject the truest passion if it is not in harmony with the vague voices in your heart – that I know. If my lot, as decided by you, must be adverse to my hopes, Mademoiselle, let me appeal to the delicacy of your maiden soul and the ingenuous compassion of a woman to burn my letter. On my knees I beseech you to forget all! Do not mock at a feeling that is wholly respectful, and that is too deeply graven on my heart ever to be effaced. Break my heart, but do not rend it! Let the expression on my first love, a pure and youthful love, be lost in your pure and youthful heart! Let it die there as a prayer rises up to die in the bosom of God!

I owe you much gratitude: I have spent delicious hours occupied in watching you, and giving myself up to the faint dreams of my life; do not crush these long but transient joys by some girlish irony. Be satisfied not to answer me. I shall know how to interpret your silence; you will see me no more. If I must be condemned to know for ever what happiness means, and to be for ever bereft of it; if, like a banished angel, I am to cherish the sense of celestial joys which bound for ever to a world of sorrow – well, I can keep the secret of my love as well as that of my griefs. – And farewell!

Yes, I resign you to God, to whom I will pray for you, beseeching Him to grant you a happy life; for even if I am driven from your heart, into which I have crept by stealth, still I shall ever be near you. Otherwise, of what value would the sacred words be of this letter, my first and perhaps my last entreaty? If I should ever cease to think of you, to love you whether in happiness or in woe, should I not deserve my punishment?

II

You are not going away! And I am loved! I, a poor, insignificant creature! My beloved Pauline, you do not yourself know the power of the look I believe in, the look you gave me to tell me that you had chosen me – you so young and lovely, with the world at your feet!

To enable you to understand my happiness, I should have to give you a history of my life. If you had rejected me, all was over for me. I have suffered too much. Yes, my love for you, my comforting and stupendous love, was a last effort of yearning for the happiness my soul strove to reach – a soul crushed by fruitless labour, consumed by fears that make me doubt myself, eaten into by despair which has often urged me to die. No one in the world can conceive of the terrors my fateful imagination inflicts on me. It often bears me up to the sky, and suddenly flings me to earth again from prodigious heights. Deep-seated rushes of power, or some rare and subtle instance of peculiar lucidity, assure me now and then that I am capable of great things. Then I embrace the universe in my mind, I knead, shape it, inform it, I comprehend it – or fancy that I do; then suddenly I awake – alone, sunk in blackest night, helpless and weak; I forget the light I saw but now, I find no succour; above all, there is no heart where I may take refuge.

This distress of my inner life affects my physical existence. The nature of my character gives me over to the raptures of happiness as defenceless as when the fearful light of reflection comes to analyse and demolish them. Gifted as I am with the melancholy faculty of seeing obstacles and success with equal clearness, according to the mood of the moment, I am happy or miserable by turns.

Thus, when first I met you, I felt the presence of an angelic nature, I breathed an air that was sweet to my burning breast, I heard in my soul the voice that never can be false, telling me that here was happiness; but perceiving all the barriers that divided us, I understood for the first time what worldly prejudices were; I understood the vastness of their pettiness, and these difficulties terrified me more than the prospect of happiness could delight me. At once I felt the awful reaction which casts my expansive soul back on itself; the smile you had brought to my lips suddenly turned to a bitter grimace, and I could only strive to keep calm, which my soul was boiling with the turmoil of contradictory emotions. In short, I experienced that gnawing pang to which twenty-three years of suppressed sigh and betrayed affections have not inured me.

Well, Pauline, the look by which you promised that I should be happy suddenly warmed my vitality, and turned all my sorrows into joy. Now, I could wish that I had suffered more. My love is suddenly full-grown. My soul was a wide territory that lacked the blessing of sunshine, and your eyes have shed light on it. Beloved providene! you will be all in all to me, orphan as I am, without a relation but my uncle. You will be my whole family, as you are my whole wealth, nay, the whole world to me. Have you not bestowed on me every gladness man can desire in that chaste – lavish – timid glance?

You have given me incredible self-confidence and audacity. I can dare all things now. I came back to Blois in deep dejection. Five years of study in the heart of Paris had made me look on the world as a prison. I had conceived of vast schemes, and dared not speak of them. Fame seemed to me a prize for charlatans, to which a really noble spirit should not stoop. Thus, my ideas could only make their way by the assistance of a man bold enough to mount the platform of the press, and to harangue loudly the simpletons he scorns. This kind of courage I have not. I ploughed my way on, crushed by the verdict of the crowd, in despair at never making it hear me. I was at once too humble and too lofty! I swallowed my thoughts as other men swallow humiliations. I had even come to despise knowledge, blaming it for yielding no real happiness.

But since yesterday I am wholly changed. For your sake I now covet every palm of glory, every triumph of success. When I lay my head on your knees, I could wish to attract to you the eyes of the whole world, just as I long to concentrate in my love every idea, every power that is in me. The most splendid celebrity is a possession that genius alone can create. Well, I can, at my will, make for you a bed of laurels. And if the silent ovation paid to science is not all you desire, I have within me the sword of the Word; I could run in the path of honour and ambition where others only crawl.

Command me, Pauline; I will be whatever you will. My iron will can do anything – I am loved! Armed with that thought, ought not a man to sweep everything before him? The man who wants all can do all. If you are the prize of success, I enter the lists to-morrow. To win such a look as that you bestowed on me, I would leap the deepest abyss. Through you I understand the fabulous achievements of chivalry and the most fantastic tales of the Arabian Nights. I can believe now in the most fantastic excesses of love, and in the success of a prisoner’s wildest attempt to recover his liberty. You have aroused the thousand virtues that lay dormant within me – patience, resignation, all the powers of my heart, all the strength of my soul. I live by you and – heavenly thought! – for you. Everything now has a meaning for me in life. I understand everything, even the vanities of wealth.

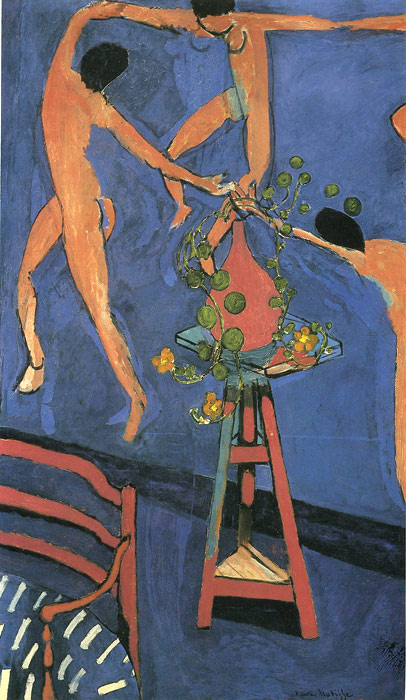

I find myself shedding all the pearls of the Indies at your feet; I fancy you reclining either on the rarest flowers, or on the softest tissues, and all the splendour of the world seems hardly worthy of you, for whom I would I could command the harmony and the light that are given out by the harps of seraphs and the stars of heaven! Alas! a poor, studious poet, I offer you in words treasures I cannot bestow; I can only give you my heart, in which you reign for ever. I have nothing else. But are there no treasures in eternal gratitude, in a smile whose expression will perpetually vary with perennial happiness, under the constant eagerness of my devotion to guess the wishes of your loving soul? Has not one celestial glance given us assurance of always understanding each other?

I have a prayer now to be said to God every night – a prayer full of you: ‘Let my Pauline be happy!’ And will you fill all my days as you now fill my heart?

Farewell, I can but trust you to God alone!

(Honoré de Balzac, Louis Lambert, pp. 242-8 in Séraphita, Dedalus 1995, translated by Clara Bell.)

Moksheungming

moksheungming@yahoo.com

2007.04.05