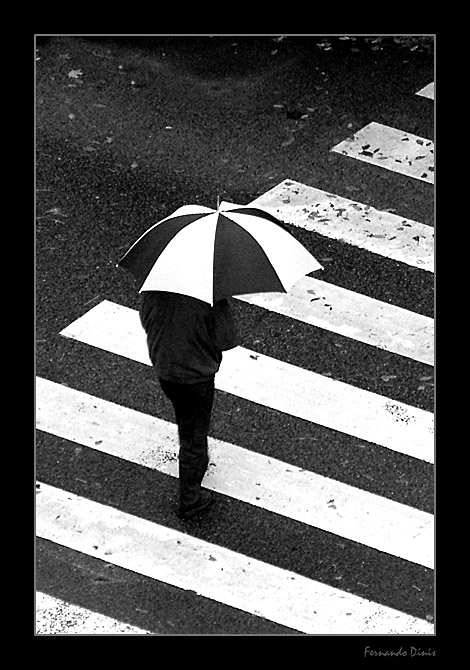

Houri in a seraglio

Des Lupeaulx was coming to that age when men have excessive pretensions with regard to women. The first gray hairs usher in the last passions, the most violent because they are astride waning power and dawning weakness. Forty is the age of folly – an age when a man wants to be loved for himself; for now his love does not hold up all by itself, as in the early years, when one can love wastefully and with impunity, even as a cherubim. At forty, one wants it all, as one is so afraid of not getting anything; whereas at twenty-five, one has so much, one does not know how to want anything. At twenty-five, one walks with such strength that one gives out with impunity; but at forty, one mistakes abuse for virility.(de Balzac, The Bureaucrats, Northwestern University Press 1993, pp. 60-1)

When a man is fifty, the Graces claim payment. At that age love becomes vice; insensate vanities come into play. Thus, at about that time, Adeline saw that her husband was incredibly particular about his dress; he dyed his hair and whiskers, and wore a belt and stays. He was determined to remain handsome at any cost. This care of his person, a weakness he had once mercilessly mocked at, was carried out in the minutest details.

(de Balzac, Cousin Bette, Everyman’s Library edition, pp. 31-2)

Lisbeth Fischer had the sort of strangeness in her ideas which is often noticeable in characters that have developed late, in savages, who think much and speak little. Her peasant’s wit had acquired a good deal of Parisian asperity from hearing the talk of workshops and mixing with workmen and workwomen. She, whose character had a marked resemblance to that of the Corsicans, worked upon without fruition by the instincts of a strong nature, would have liked to be the protectress of a weak man; but, as a result of living in the capital, the capital had altered her superficially. Parisian polish became rust on his coarsely tempered soul. Gifted with a cunning which had become unfathomable, as it always does in those whose celibacy is genuine, with the originality and sharpness with which she clothed her ideas, in any other position she would have been formidable. Full of spite, she was capable of bringing discord into the most united family.

In early days, when she indulged in certain secret hopes which she confided to none, she took to wearing stays, and dressing in the fashion, and so shone in splendour for a short time, that the Baron thought her marriageable. Lisbeth at that stage was the piquante brunette of old-fashioned novels. Her piercing glance, her olive skin, her reed-like figure, might invite a half-pay major; but she was satisfied, she would say laughing, with her own admiration.

And, indeed, she found her life pleasant enough when she had freed it from practical anxieties, for she dined out every evening after working hard from sunrise. Thus she had only her rent and her midday meal to provide for; she had most of her clothes given her, and a variety of very acceptable stores, such as coffee, sugar, wine, and so forth.

In 1837, after living for twenty-seven years, half maintained by the Hulots and her Uncle Fischer, Cousin Bette, resigned to being nobody, allowed herself to be treated so. She herself refused to appear at any grand dinners, preferring the family party, where she held her own and was spared all slights to her pride.

Wherever she went – at General Hulot’s, at Crevel’s, at the house of the young Hulots, or at Rivet’s and at the Baroness’s table – she was treated as one of the family; in fact, she managed to make friends of the servants by making them an occasional small present, and always gossiping with them for a few minutes before going into the drawing-room. The familiarity, by which she uncompromisingly put herself on their level, conciliated their servile good-nature, which is indispensable to a paradise. ‘She is a good, steady woman,’ was everybody’s verdict.

Her willingness to oblige, which knew no bounds when it was not demanded of her, was indeed, like her assumed bluntness, a necessity of her position. She had at length understood what her life must be, seeing that she was at everybody’s mercy; and needing to please everybody, she would laugh with young people, who liked her for a sort of wheedling flattery which always wins them; guessing and taking part with their fancies, she would make herself their spokeswoman, and they thought her a delightful

Her absolute secrecy also won her the confidence of their seniors; for, like Ninon, she had certain manly qualities. As a rule, our confidence is given to those below rather than above us. We employ our inferiors rather than our betters in secret transactions, and they thus become the recipients of our inmost thoughts, and look on at our meditations; Richelieu thought he had achieved success when he was admitted to the Council. This penniless woman was supposed to be so dependent on every one about her, that she seemed doomed to perfect silence. She herself called herself the Family Confessional.

It may here be well to add that the Baron’s house preserved all its magnificence in the eyes of Lisbeth Fischer, who was not struck, as the parvenu perfumer had been, with the penury stamped on the shabby chairs, the dirty hangings, and the ripped silk. The furniture we live with is in some sort like our own person; seeing ourselves every day, we end, like the Baron, by thinking ourselves but little altered, and still youthful, when others see that our head is covered with chinchilla, our forehead scarred with circumflex accents, our stomach assuming the rotundity of a pumpkin. So these rooms, always blazing in Bette’s eyes with the Bengal fire of Imperial victory, were to her perennially splendid.

As time went on, Lisbeth had contracted some rather strange old-maidish habits. For instance, instead of following the fashions, she expected the fashion to accept her ways and yield to her always out-of-date notions. When the Baroness gave her a pretty new bonnet, or a gown in the fashion of the day, Betty remade it completely at home, and spoilt it by producing a dress of the style of the Empire or of her old Lorraine costume. A thirty-franc bonnet came out a rag, and the gown a disgrace. On this point, Lisbeth was as obstinate as a mule; she would please no one but herself, and believed herself charming; whereas this assimilative process – harmonious, no doubt, in so far as that it stamped her for an old maid from head to foot – made her so ridiculous, that, with the best will in the world, no one could admit her on any smart occasion.

(ibid, pp. 37-40)

The moralist cannot deny that, as a rule, well-bred though very wicked men are far more attractive and lovable than virtuous men; having crimes to atone for, they crave indulgence by anticipation, by being lenient to the shortcomings of those who judge them, and they are thought most kind. Though there are no doubt some charming people among the virtuous, Virtue considers itself fair enough, unadorned, to be at no pains to please; and then all really virtuous persons, for the hypocrites do not count, have some slight doubts as to their position; they believe that they are cheated in the bargain of life on the whole, and they indulge in acid comments after the fashion of those who think themselves unappreciated.

(ibid, p. 54-5)

This modern art of love uses a vast amount of evangelical phrases in the service of the Devil. Passion is martyrdom. Both parties aspire to the Ideal, to the Infinite; love is to make them so much better. All these fine words are but a pretext for putting increased ardour into the practical side of it, more frenzy into a fall than of old. This hypocrisy, a characteristic of the times, is a gangrene in gallantry. The lovers are both angels, and they behave, if they can, like two devils.

(ibid, p. 106)

You will always see my unhappiness increase in proportion to the circumference of the social spheres I enter. How many efforts did I not make to rescind the sentence which condemned me to live only within myself! How many hopes, slowly formulated with a thousand leaps of spirit, were dashed in a single day!

(de Balzac, Lily of the Valley, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 2nd edition, 1989: p. 6)

It would displease you if I gave flat waists the advantage over rounded waists, were you not an exception. The rounded waist is a sign of strength, but women so built are imperious, wilful, and more sensual than tender. Conversely, flat-waisted women are devoted, eminently sensitive and inclined to melancholy. They are more womanly than the others. The flat waist is soft and yielding, the rounded is inflexible and jealous.

(ibid, p. 27)

’My dear, you do not know how much insolence a woman like my mother can put into a patronising look, how much abasement in a word, how much scorn in a greeting!’

(ibid, p. 96)

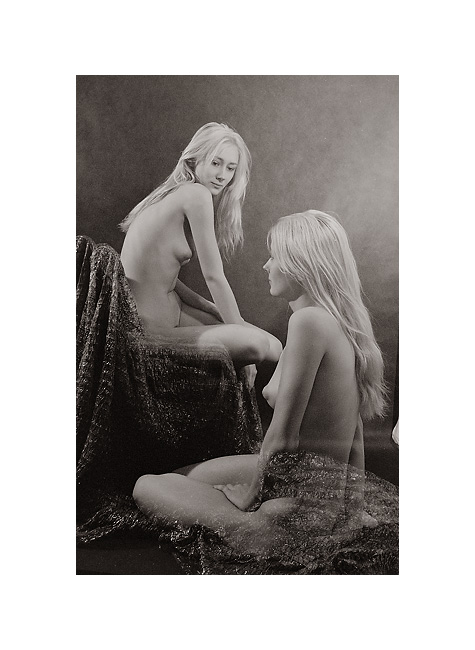

Her procedure, as you see, was directed at my pride; she flattered a man’s every vanity by deifying it; she set me so high that she could live only at my feet. Moreover, all the blandishments her mind could conceive were expressed by her submissive slave-girl pose and by her total subjection. She could spend the entire day lying on the floor at my feet, without saying a word, looking at me, biding her time until the hour of pleasure like an houri in a seraglio and bringing it forward with artful coquetry, while giving every impression that she was patiently awaiting it. With what words can I describe those first six months during which I was a prey to the enervating joys of a love, fruitful in its delights and varying them with the ability born of experience, while hiding its learned skill behind the transport of passion? These pleasures, sudden revelation of the poetry of the senses, constitute the vigorous bond that fastens young men to women older than themselves; but this link is the convict’s ball and chain; it leaves an indelible mark upon the soul; it gives it a distaste for fresh and candid loves, rich in flowers only, who do not know how to serve alcohol in curiously wrought cups of gold, studded with gems that flash with inexhaustible fires.

(ibid, pp. 176-7)

’Henriette, there are mysteries in a man’s life which you know nothing of. I met you at an age when sentiment can stifle the desires prompted by our nature; but many scenes, whose memory will warm me at the hour of death, must have shown you that that time was drawing to an end and your eternal triumph has been that you prolonged its unspoken delights. A love without possession is sustained by the very exacerbation of desire; then there comes a moment when we are one continuous ache, we who are so utterly unlike you. We have a potency from which we cannot abdicate, on pain of ceasing to be men. Deprived of the nourishment that should sustain it, the heart feeds on itself and experiences a drained lassitude which is a kind of forerunner of death. Nature cannot be thwarted for long: at the slightest accident it awakens with an energy akin to madness. No, I have not tasted true love, but I have thirsted in the middle of the desert.’

(ibid, pp. 187-8)

Who could resist the deflowering mind of Louis XVIII, who used to say that men only know true passion in their riper middle years, since passion is only fine and furious when impotence plays a part in it, and when one meets each pleasure like a gambler placing his bet? At the end of the avenue, I turned and glanced back, to find that Henriette was still there, alone! I went back to say a last farewell, bathed with atoning tears whose cause was hidden from her. Genuine tears, devoted unknowingly to those fair hours of love forever lost, to these virgin emotions, those flowers of life that never bud again: for later on, man no longer gives, he receives; he loves himself in his mistress: while in youth he loves his mistress in himself. Later, we inject our tastes, our vices too, perhaps, into the woman we love; whereas at the beginning of life the one we love gives us her virtues and her tender conscience. She beckons us to the good life with a smile and teaches us devotion by her example. Woe to the man who never had his Henriette!

(ibid, p. 212)

Moksheungming

moksheungming@yahoo.com

2007.02.02